Nematodes From the Siberian Permafrost Woke Up After a 46,000 Year Long Nap

The general consensus among us mammals is that if we get very cold, we die. Within the world of nematodes, however, they’d like to differ on that viewpoint. This is demonstrated succinctly after researchers coaxed a batch of these worms back into action after they had been frozen in Siberian permafrost for an estimated 46,000 years. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon is called cryptobiosis, which is essentially a metabolic state that certain lifeforms can enter when environmental conditions become unsuitable.

In the case of nematodes, they hold a number of records, with a group of them having survived the STS-107 Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003 when it broke up during reentry, making it the first known lifeform to have achieved such a feat. During arctic experiments it was found that these roundworms can withstand intracellular freezing even while active depending on its diet.

For these particular permafrost nematodes, they offer us a glimpse at a species of nematodes that hasn’t been around for thousands of years, with phylogenetic analysis indicating them to be related to current species in the Panagrolaimus and Plectus genera, but different enough to receive the new name of Panagrolaimus kolymaensis. In the paper, the researchers describe how they performed experiments on C. elegans nematode larvae to compare its cryptobiosis capabilities and found both to be comparable, although P. kolymaensis shows a stronger ability to protect its cell membranes, which is ultimately key for long-term survival while frozen.

An interesting aspect of nematodes is that some of them are hermaphrodites, meaning that they can reproduce asexually. Combined with an ability to stay dormant across geological timescales, this makes these small worms incredibly hardy survivors that’d give cockroaches a run for their exoskeleton.

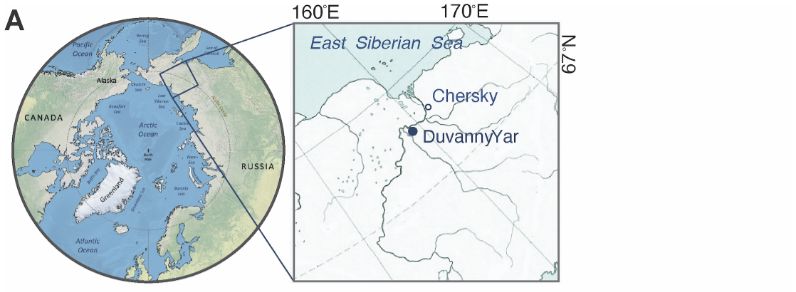

(Heading image: Location of the Duvanny Yar outcrop on the Kolyma River, northeastern Siberia, where the nematodes were found. (Credit: Anastasia Shatilovich et al., 2023))

from Blog – Hackaday https://ift.tt/q7hP802

Comments

Post a Comment