Teardown: Sling Adapter

The consumer electronics space is always in a state of flux, but perhaps nowhere is this more evident than with entertainment equipment. In the span of just a few decades we went from grainy VHS tapes on 24″ CRTs to 4K Blu-rays on 70″ LED panels, only to end up spending most of our viewing time watching streaming content on our smartphones. There’s no sign of things slowing down, either. In fact they’re arguably speeding up. Sure that 4K TV you bought a couple years back might have HDR, but does it have HDMI 2.1 and Dolby Vision?

So it’s little surprise that eBay is littered with outdated A/V gadgets that can be had for a pennies on the dollar. Take for example the SB700-100 Sling Adapter we’re looking at today. This device retailed for $99 when it was released in 2010, and enabled Dish Network users to stream content saved on their DVR to a smartphone or tablet. Being able to watch full TV shows and movies on a mobile device over the Internet was a neat trick back then, before Netflix had even started rolling out their Android application. But today it’s about as useful as an HD-DVD drive, which is why you can pick one up for as little as $5.

Of course, that’s only a deal if you can actually do something with the device. Contemporary reviews seemed pretty cagey about how the thing actually worked, explaining simply that plugging it into your Dish DVR imbued the set-top box with hitherto unheard of capabilities. They assured the reader that the performance was excellent, and that it would be $99 well spent should they decide to dive headfirst into this brave new world where your favorite TV shows and movies could finally be enjoyed in the bathroom.

Of course, that’s only a deal if you can actually do something with the device. Contemporary reviews seemed pretty cagey about how the thing actually worked, explaining simply that plugging it into your Dish DVR imbued the set-top box with hitherto unheard of capabilities. They assured the reader that the performance was excellent, and that it would be $99 well spent should they decide to dive headfirst into this brave new world where your favorite TV shows and movies could finally be enjoyed in the bathroom.

Now, more than a decade after its release, we’ll crack open the SB700-100 Sling Adapter and see if we can’t figure out how this unusual piece of tech actually worked. Its days of slinging the latest episode of The Office may be over, but maybe this old dog can still learn a few new tricks.

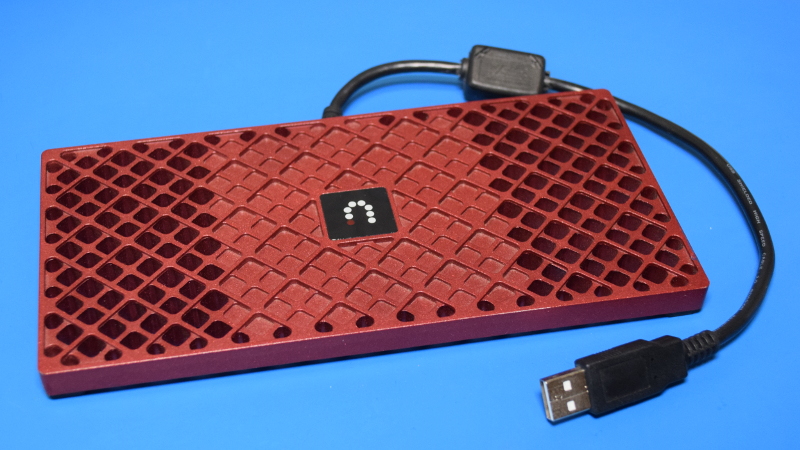

A Crimson Enigma

To be sure, the Sling Adapter is a very unusual device. It has no controls, no display, and its only link to the outside world is the short USB pigtail that’s permanently attached to the rear of the unit. Yet despite its apparent simplicity, its heat-dissipating metal enclosure hints at considerable raw power underneath its Merlot hood. Even today the device looks impressively high-tech, which may explain why the reviewers from the previous decade were so enamored with it. If the Sling Adapter looks like some piece of advanced technology now, imagine what they thought of it in 2010.

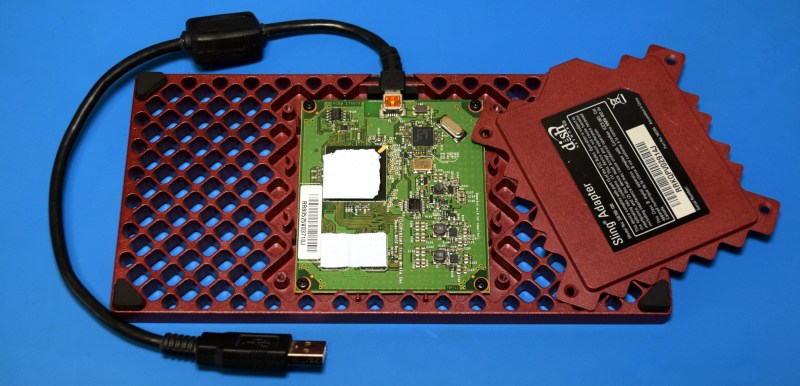

Upon opening up the device we’re greeted with a healthy application of thermal compound, which confirms that the metallic grid case is essentially a massive heatsink. With the removal of four more screws, the 70 mm x 80 mm PCB can be lifted out of the case, and surprisingly, the USB pigtail can be disconnected from what turns out to be a female Mini-B jack. As far as disassembly goes, it surely doesn’t get much easier than this. But of course, we’ve still got to figure out what this board does.

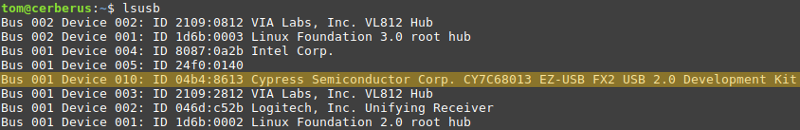

Before I went any farther and potentially damaged something, I decided it would be wise to plug the board into the computer to see what happens. We’ve found unexpected USB functionality in previous teardowns, but even still, I’ll admit to being momentarily stunned by the output of lsusb.

Incredibly, the Sling Adapter was immediately recognized as a Cypress CY7C68013 EZ-USB FX2 Development Kit. The EZ-USB FX2 pairs an Intel 8051 microcontroller with a high-speed USB 2.0 interface that’s designed to facilitate bulk transfers and has the ability to renumerate itself on the fly. A bit of digging uncovers that firmware for the chip is generally downloaded from the host system and copied into RAM on power-up, after which point the code is executed and the USB parameters readjust as necessary for the new application.

It would appear that, accidentally or otherwise, the Sling Adapter’s default state is to advertise itself as a development board until a firmware image has been provided by the Dish DVR. My first thought was that the device might be operating as sort of a security dongle, where the DVR would upload some code to it and wait to see if it gets the appropriate response after execution. But the device wouldn’t be generating the sort of heat its’s clearly been designed for if it was just calculating some checksums; obviously there’s some serious number crunching going on.

H.264 on a Chip

After spending some quality time with cotton swabs and isopropyl alcohol, we have our answer. Hidden under the thick layer of thermal compound is a Magnum DX6225-LHG00-A3 that was designed to transcode MPEG-2 video to a lower-resolution H.264 stream suitable for playback on early smartphones and tablets. The two identical chips next to it are obviously external RAM, but I’ve been having some trouble identifying them conclusively. My best guess is that they are Micron 8 MB MT47R64M16’s with some alternate branding, but even for 2010, 16 MB of RAM seems pretty low.

Combined with the bulk transfer capabilities of the EZ-USB FX2, things are starting to make sense. The Dish DVR pushes the MPEG-2 video stored on its hard drive to the DX6225 over USB, where its transcoded in real-time to a mobile friendly format and sent back to the set-top box where it’s ultimately distributed over the network.

It’s a concept we still see in use today, albeit with considerably different workloads. The Coral USB Accelerator and Intel Neural Compute Stick are essentially modern answer to the Sling Adapter; plug-in modules that handle the computational workload of machine learning so the host system can focus on the logistics and user interface. This helps performance-constrained “edge” platforms such as the Raspberry Pi handle tasks like high-framerate computer vision, and back in 2010, it let Dish subscribers play videos on their phones without bogging down the DVR.

New Marching Orders

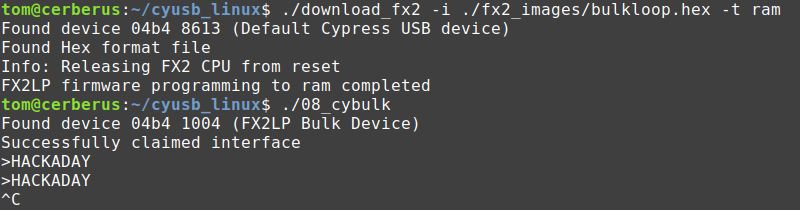

I know what you’re thinking. If the USB side of the Sling Adapter is really based on a Cypress CY7C68013 EZ-USB FX2 development kit, does that mean you can buy one of these things for $5 and load new code into its 8051 MCU? The answer, at least so far, would appear to be yes. But as usual, the Devil is in the details.

After compiling the open source cyusb linux suite, I was successfully able to connect to the EZ-USB FX2 and upload one of the included demonstration firmware images into RAM. After the Sling Adapter renumerated, a program running on the computer was able to establish a loop-back connection with the firmware. While I haven’t personally tested it yet, you should be able to use the official (and relatively modern) EZ-USB FX3 Software Development Kit from Cypress to start writing your own firmware as its backwards compatible with FX2.

Now for the bad news. Remember how I said the Sling Adapter doesn’t have any controls or displays? Unfortunately, that doesn’t make it a very exciting platform for experimenting with. Sure you can get it to run your own code, but this is a machine built for a very specific purpose, so there’s not much that code can actually do. Though if you do manage to create a custom firmware for these things that does something interesting, we’d certainly love to hear about it.

from Blog – Hackaday https://ift.tt/3oilqvd

Comments

Post a Comment